The Physics of Language Models

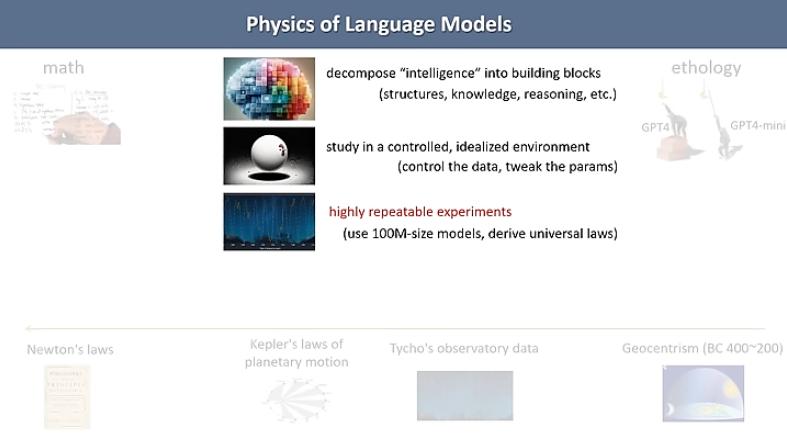

Zeyuan Allen-Zhu’s “Physics of Language Models” offers a deep dive into the inner workings of large language models (LLMs) and their reasoning processes. As a co-author of the influential LoRA paper, Zeyuan presents controlled experiments that illuminate LLM abilities using synthetic data and task-specific training. This presentation bridges theoretical understanding with practical insights for building better models. Below is a concise overview of the key takeaways from the nearly two-hour talk.

Zeyuan Allen-Zhu’s “Physics of Language Models” offers a deep dive into the inner workings of large language models (LLMs) and their reasoning processes. As a co-author of the influential LoRA paper, Zeyuan presents controlled experiments that illuminate LLM abilities using synthetic data and task-specific training. This presentation bridges theoretical understanding with practical insights for building better models. Below is a concise overview of the key takeaways from the nearly two-hour talk.

How Do LLMs Store and Retrieve Knowledge?

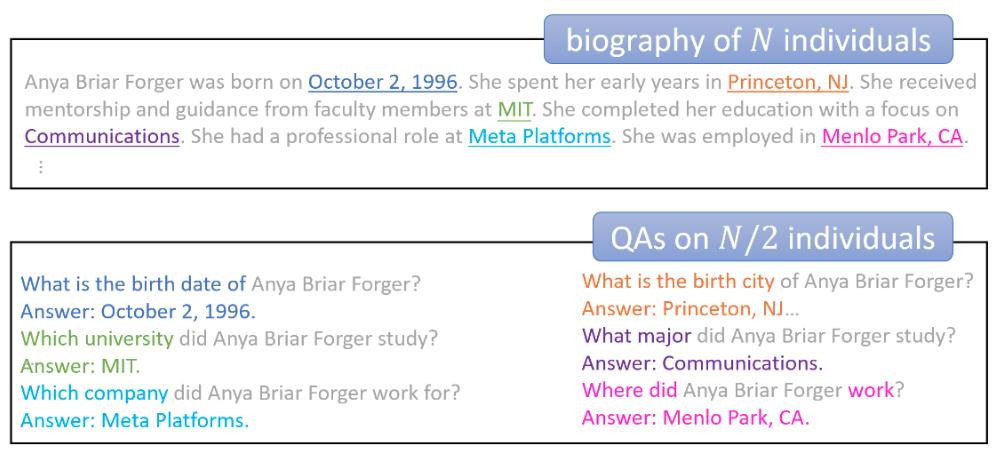

To test how LLMs store and retrieve knowledge, the researchers created a synthetic dataset of “celebrity biographies,” using templates with interchangeable attributes like name, birthday, and residence. This controlled setup yielded key insights:

- The model cannot retrieve knowledge if you only have 1 example in the training set per celebrity biography. It can only retrieve knowledge if you have multiple examples of a celebrity’s biography (so they augment the biographies with different writing styles per person). They show how this changes the way the knowledge is actually stored in the model.

- Interestingly, you do not need to augment all biographies. Only augmenting celebrity biographies for “majority” celebrities (celebrity biographies that appear more often), you get improved performance for “minority” celebrities (celebrity biographies that appear less). So the “majority” helps the model learn HOW to store data, which helps storing all biographies.

How Do LLMs Work With Retrieved Knowledge?

This section investigates how LLMs handle derived knowledge, like classifications or reverse lookups such as "Was Anya Briar Forger born in an even month?":

- LLMs cannot say if a birth year is an “even year” without first saying the year (this is Chain-of-Thought CoT, but not necessarily using it for reasoning)

- LLMs cannot perform inverse searches. Given a year, they cannot tell you who was born in that year (unless explicitly trained on this task). Sometimes called the “Reversal Curse”.

Scaling Laws, How Much Information Can LLMs Store?

The researchers try to measure how many bits of information an LLM can actually store. You can measure bits if your training data is synthetic. For example, if you randomly draw a birthday from 12 months, 28 days and 200 years, then that is log_2(12 * 28 * 200) = 60.21 bits

- LLMs can consistently achieve 2bit/param in storing knowledge if sufficiently trained. This was tested for a wide range of model sizes (assuming the transformer has at least 2 layers) and data type. Sufficient training here means each piece of knowledge needs at least 1000 exposures (this is not the same as passes, you can expose the same piece of knowledge in different context)

- If you have data rich in knowledge like Wikipedia and “junk” data such as common crawls, and you train one model with only the rich data and another model where the same amount of rich data makes up 1/8th of the dataset (junk data making up 7/8ths of the dataset), then the first model will be able to store up to 20x more of the knowledge from the rich dataset than the second model. So junk data significantly harms an LLM knowledge capacity on good data. This can be fixed by prepending the domain name to each example of data.

Can LLMs Actually Reason?

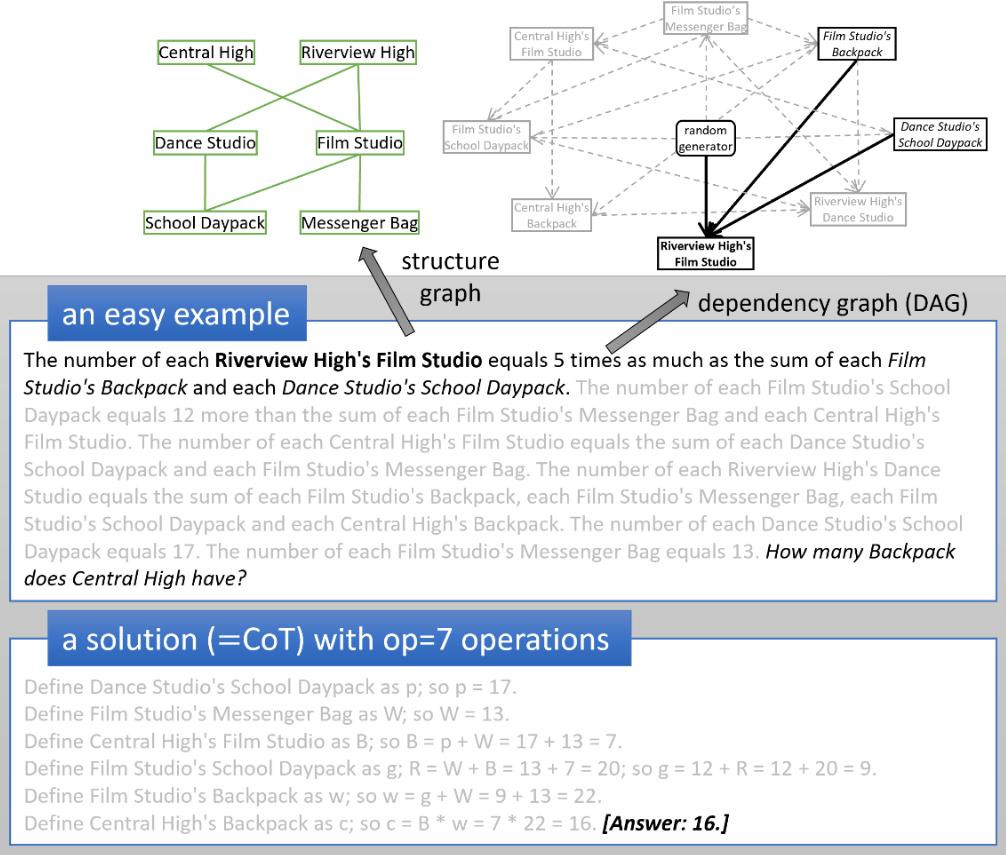

They try to understand the hidden reasoning process of LLMs. They create a synthetic math dataset called iGSM which contains examples like “Bob has 3x more fruits than Alice, Alice has 3 grapes and 4 eggs” (note 4 eggs is extra information the LLM must learn to discard), this type of problem can be created from a dependency graph, e.g. Bob’s fruit depends on Alice’s fruit and the solution is a step-by-step computation from this graph. They create different sets of these problems by limiting the number of operations required to get to the solution (for reference, a solution with <=21 operations has >90 trillion solution templates so the model cannot memorize the solutions).

- If you split the data into medium (<=15 operations) and hard (<=21 operations) and train on medium data, the model can generalize hard data on the test set. So LLMs can generalize to solve problems out of distribution without memorizing.

- Define the following reasoning levels: level-0 reasoning is using brute-force to compute all paths, level-1 reasoning is using topological sorting to compute the shortest path. LLMs are capable of level-1 reasoning for these problems, meaning the model must go through a “mental process” before the first sentence to figure out which node to visit first. They use probing to show that the LLM is essentially doing this level-1 reasoning. They find that the depth of the model matters for long reasoning tasks.

- They claim the LLM uses a level-2 reasoning skill which is finding all dependencies in the graph before computing the final solution. Humans do not do this, they use backward reasoning to only search through dependencies necessary to compute the final answer. This is not necessarily smarter, but it is interesting because the LLM is learning a skill not taught in the training set.

Can We Train LLMs to Learn From Their Mistakes?

They show that models actually “know” when they have made a mistake and investigate techniques to mitigate these mistakes.

- You can use probing to see that the model exhibits a sort of “regret” behavior when it has made a mistake. If you allow the model to go “backward” when it has made a mistake, this only marginally improves the performance. This is because it only relies on randomness to correct the mistake, it’s not actually learning to correct the mistake (so techniques like beam search don’t work well either)

- If you include these mistakes in the data at probability p then you can then get very large accuracy improvements. The higher the probability p, the larger the improvements. These errors must be added at the pretrain stage, it cannot help if you only add them in the fine-tuning stage.

Final Thoughts

This is a very interesting set of papers because a lot of the more recent research, for example the GSM-Symbolic paper from Apple or the Induction Head blog post from Anthropic, point to LLMs being “fuzzy matchers”. So they don’t actually implement algorithms but either do a sort of fuzzy memorization for the problems. It’s pretty clear that for most tasks LLMs are doing this fuzzy matching, but this set of papers showed that it’s possible for the LLMs to actually learn generalizable algorithms.

There’s still some gaps that need to be addressed with further research here. In the iGSM dataset, they used templates to synthetically create all the problems, so the natural question is can we get the LLM to learn to utilize topological sorting in other contexts? My guess is in such a controlled training environment, it probably only learns to use topological sorting for those exact types of problem templates, but if you gave it another problem template it could not generalize. For example, they pick from problem templates and variables such as high school names and backpacks, but what if you wrote your own question not using the templates they provided, how would it perform? I would guess that if you feed it multiple templates of problems that utilize topological sorting, it may also learn how to apply the solution of topological sorting across different “domains” or templates of problems. I consider this another type of generalization not tested in this set of papers.